- Review: 2:22 starring Cheryl; A Ghost Story that’s, ironically, human

- Review: Orlando starring Emma Corrin; Stylish but Self-conscious

- Review: Least Like the Other: Searching for Rosemary Kennedy; “Lobotomy: The Opera”!

- Review: Matthew Bourne’s Sleeping Beauty; A Fever Dream Fairytale

- Review: Hakawatis, Women of the Arabian Nights; Intimate Storytelling in Female Gaze at Shakespeare’s Globe

- Best of the Year: Review: My Neighbour Totoro; Some High End Puppets

-

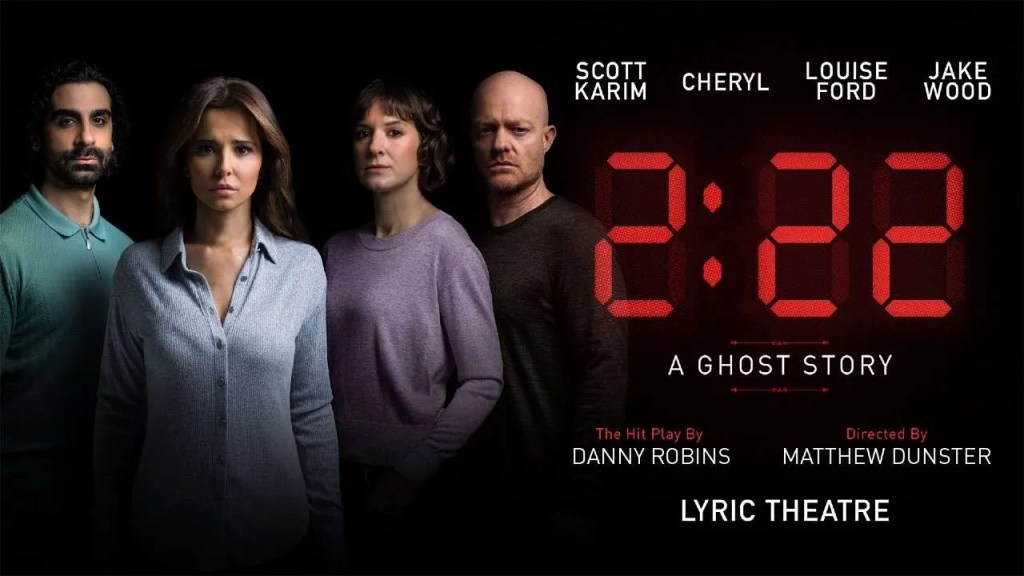

Review: 2:22 starring Cheryl; A Ghost Story that’s, ironically, human

2:22 achieves the most impressive feat in the horror genre: a satisfying ending.

As applause subsides, I ask around “Did you guess the ending?” From hushed near whispers to bursts of enthusiasm, the answer is unanimously “no.”

Further impressive, audiences are still surprised in this, 2:22’s 5th West End run.

(I conducted the same informal poll after experiencing the shock myself in its first run starring Lily Allen.)

Advertisements

AdvertisementsThe writing is excellent. Danny Robins carefully crafts a narrative that is an engrossing ghost story, a meditative psychological exploration, and a test of human relationships. Watching a second time, I appreciate the clever clues even more. (No spoilers here, but DM me to chat dead giveaways.)

At its core, 2:22 is, ironically, human.

Jenny invites her husband’s old uni friend and new boyfriend to a dinner party with an ulterior motive. She’s been hearing a ghost in her newborn’s nursery every night exactly at 2:22. Jenny is intent on convincing her husband and the skeptical couple to stay awake with her to witness the ghost. As the clock ticks, bold and red onstage, will their wits last until 2:22?

The ghost story itself is very nearly a supporting character to this daring double date. The story is most engrossing as the relationships splinter. Robins mixes pairs with scenes that expertly unravel the nuances between the husband and the old flame-cum-life-long-friend, between Jenny and the friend, between the skeptical male characters, and between two female characters in search of emotional certainty. The writing interrogates how we put build and express trust in relationships, old and new.

Ghost stories have always been a push and pull between science and emotion. These relationship tug at this tension, pulling the knot of doubt tighter.

Cheryl impressively holds the duality of these emotions throughout her performance. She is scared but stubborn. She is unsure but confident. She is calm but frayed.

Cheryl delivers a solid and consistent performance. Her characterisation is relatable and draws the audience in.

For an acting debut, Cheryl delivers. But one critique stays with me in the room.

Advertisements

Cheryl is a better solo artist than an ensemble performer. Cheryl delivers her lines and characters convincingly, but is missing that spark of chemistry between her husband and her fellow cast mates. At the beginning of its run, this chilly foursome still has time to warm up.

Even so, 2:22 is a durable piece of writing that breaths anew with each new West End rebirth. See it once—or twice—if you can.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsAll images are promotional photos from 2:22 and Helen Murray.

-

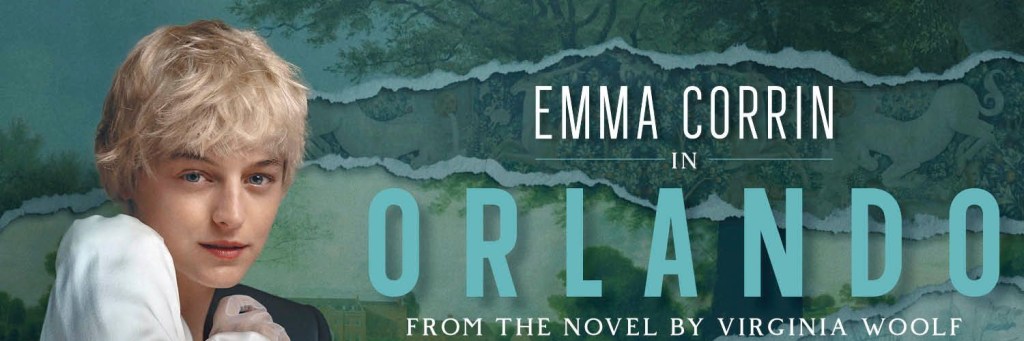

Review: Orlando starring Emma Corrin; Stylish but Self-conscious

Emma Corrin is a paper doll. One costume peels off as another is pasted on. Before settling into an identity, it gives way to the next. Orlando, Corrin’s character in the eponymous play, lives a life that spans over 300 years, traverses land and sea, and fluidly navigates gender. Corrin, ever the shape-shifter, effortlessly plays the part.

Virginia Woolf’s late 1920s novel, Orlando: A Biography is often hailed as one of first trans novels. Translated to stage, Orlando is a bold choice that meets the moment. Orlando speaks to the present, while stripping back to reveal the deep roots of centuries-old conversations on gender, sexuality, and power. Emma Corrin, one of the most famous non-binary actors of the silver screen, easily embodies Orlando. It’s clearly a winning recipe, as evidenced by the 5-star reviews and excited audience reactions.

However, Neil Bartlett’s adaption is unbalanced. It leans too heavily into the present moment, adopting Twitter-speak at the expense of Woolf’s source text. Orlando becomes an elusive character that is neither self-assured nor self-doubting. Orlando and their world is difficult to pin down. It tries to be everything at once and misses the opportunity to say anything profound.

(The first half of this review has no spoilers. Read on for my criticism of the play’s ending and an Easter egg moment, if you don’t mind a spoiler or two.)

We are introduced to Orlando who, despite being born into wealth and land in the mid-1600s, rebukes society. When Elizabeth I comes to visit, we discover Orlando has begun a journey of sexual exploration and self discovery. Unsatisfied with the expectations of marriage and Elizabethan society, Orlando sets off on his own.

This is our first time jump. We follow Orlando to the Jacobean Frost Fair where he meets a Russian princess. The relationship burns bright and fast, but the flame goes out as quickly as it begins.

Fast forwarding again, Orlando chooses to leave this life behind and become an ambassador in Constantinople. Here, instead of dying, Orlando transitions into a woman.

And thats just the first third of the play. From there, Lady Orlando continues their journey of self discovery in equally as exotic scenarios but this time without male privilege.

This Orlando is nervously self-aware. The characters over-apologise in asides to the audience, leaning into internet talk about capitalism, colonialism, class, gender, and sex. While these moments speak to profound societal truths, they’re gone as quickly as a tweet. Instead of building intellectual momentum, the play lets off steam in short bursts that leave its final scenes hanging limp.

Although the characters on stage speak of Orlando’s bold self-assured character, this is not the Orlando I see onstage. This is an anxious Orlando that experiences flashes of confidence (mostly as a man).

It’s easy to look past this surface-level presentation.

Michael Grandage’s production is stylish and modular. The costumes rely on punchy symbols of eras — Elizabethan ruffles, Jacobean puffs, Victorian corsets, while maintaining modern silhouettes. The stage itself is also modular, with set pieces added and rolled away to evoke places and periods. Orlando’s visual world adapts but never transforms.

Michael Grandage’s Orlando is stylish without much substance. Its source material follows the moderniststyle of stream of consciousness, at the expense of plot. Instead, Bartlett and Grandage choose to emphasise plot at the expense of the deep intellectualism of Woolf’s writing.

On stage, Bartlett’s and Grandage create a fast-paced adventure that captures the feeling of Britain’s historical eras, but doesn’t say much. In the end, Corrin’s compelling chameleon acting is left painting with a dull, muted palette.

Audiences will undoubtedly find quotable lines that match their personal politics. From Lady Orlando’s delight in sex with women to takedowns of exploitative colonialism to calls to action in the class struggle. Neil Bartlett’s script creates many Gif-able moments.

Audiences will equally find Emma Corrin’s Orlando relatable and approachable.

If only the entire play were as strong as its quotable moments and its star.

(Spoilers start here)

Advertisements

AdvertisementsIn its opening scenes, the Virginia Woolfs (yes there are multiple Virginia Woolfs on stage) open the play with bold questions:

“Who am I?” “Who do I love?” “Do I have to follow the rules of society?”

But in its closing scenes, the play ends with limp Pinterest platitudes:

“I am here.” “I love wine.” “Choose courage.”

The ending is rushed and inconclusive.

After spending 90 minutes on Orlando’s character development, Orlando rushes into love thoughtlessly. The entire arc of Orlando’s search for love is unmoored from emotion.

But that just addresses the plot. Worse, the larger themes of Orlando fail to land.

It’s as if Bartlett couldn’t choose between two endings.

In one interpretation of the ending, love isn’t the rigid expectation of society. In this ending, women’s lives aren’t bound to who they marry and life’s purpose isn’t achieved with marriage. In this ending, Orlando offers an emancipatory definition of love

In another interpretation, Orlando, at this point in the 1920s, is told to wait another hundred years to find freedom. Presumably this ending points to the present moment, promising more freedom in 21st century feminism.

Both are compelling ideas. Unfortunately, neither idea is fully developed.

For your consideration, these are the last 4 lines of the play:

“Who am I?

I am Orlando.

What is my favourite time?

My favourite time is right now.”

The last line of the play could be a yogic mantra, speaking directly to the self-love generation of now.

Read another way, as Orlando walks into the sunlight and offstage, the last line could mean Orlando is walking 100 years forward into next adventures, or, in other words, into the present moment.

Unfortunately, this non-specific closing moment is unsatisfying.

“What is my favourite time?”

Personally, my favourite time was the beginning half of the play, but I am happy to hear Orlando likes it right now.

(As promised, the Easter egg)

It’s widely speculated that the thoroughly modern Virginia Woolf wrote “Orlando: A Biography” about her real-life female lover, fellow author, Vita Sackville-West. Look closely at illustrations of Orlando and you’ll find their form nearly identical to photographs of Vita. Many scholars have built careers analysing and assessing what Vita-as-Orlando can tell us about the struggling writer-artist and changing attitudes across centuries.

How does this translate to stage?

Virginia Woolf is onstage for nearly the entire show. Often, there is more than one Virginia Woolf onstage, writing the dialogue, directing the scene, and, in some cases, correcting Orlando’s behaviour.

In the denouement of the play, Orlando marries a sensible and boring Englishman. By the closing scene, the Englishman has faded from view and Orlando has retaken centre stage.

The husband returns onstage, this time dressed as Virginia Woolf. Orlando is pulled off the shelf from a bookcase of Virginia Woolfs.

In the final scene, Orlando speaks to their genuine love for their husband. Stepping towards Orlando, the husband-cum-Virginia kisses Orlando under the spotlight.

Indeed, wait 100 years, Orlando, and here you will find your public debut of your relationship with Virginia in London society. A love emancipated from societal expectations and as meaningful now as it was in 1928.

The moment lasts the blink of an eye, but carries 3 centuries of love, loss, and hope in a single kiss.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsAll images are promotional photos from Michael Grandage Productions and Marc Brenner.

-

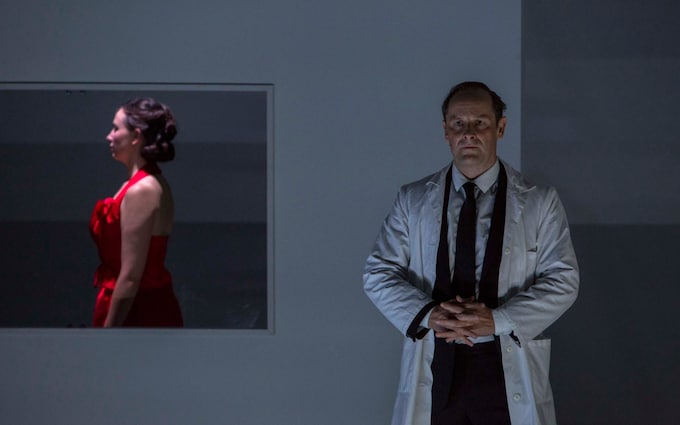

Review: Least Like the Other: Searching for Rosemary Kennedy; “Lobotomy: The Opera”!

Before the lobotomy, Rosemary Kennedy loved opera. In Irish National Opera’s Least Like the Other: Searching for Rosemary Kennedy, art imitates life in the deepest irony.

This is an opera about Rosemary Kennedy’s lobotomy. It’s medical misogyny set to music. Joe and Rose Kennedy’s gloss-finished Camelot, of which JFK was their triumph, unravels to reveal the Kennedy curse. Intelligence tests, weight loss schemes, and the oppressive push towards perfection culminate in Rosemary’s ill-fated medical procedure. The American Dream cuts towards incoherence.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsNetia Jones directs a production of profound contrasts. The opera begins with Rose Kennedy giving birth to her eldest daughter, Rosemary. We are acclimatised to Rose’s Stepford perfection through index cards and cognitive capacity tests. The tests beg their taker “Which of these is least like the other?”

Rosemary is the answer. Rosemary prefers swimming and dancing. Her most important test is learning a proper courtesy for the Queen. In a house with Joe Jr., Jack, and Robert, Rosemary is least like the others.

The frenetic frenzy of the Kennedy ambition is contrasted with interludes of release. At first, wobbling static cut the building tension as the Kennedy children prepare for IQ tests. Later, the stage fills with projections of water as Rosemary drowns in the mounting scrutiny of her mental state.

These contrasts create the emotional depth of the opera. The release is welcome. Even the static and pulsing projections outage create a sense of relief. Least is startling and upsetting, but that is what carries the operas larger themes of suffocating societal expectations.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsMusically, Brian Irvine has composed a soundscape of conflicting jazz bands. With two conductors leading two separate ensembles, the music clashes more than complements.

My ears dig through the neural pathways of the piece to find some semblance of melody, unsuccessfully. Often, the piece’s vocal lines are atonal, leaving little room for mezzo soprano Amy Ni Fherraigh to convey any emotion as Rosemary Kennedy.

Is this music or this noise? In its most orchestral, the strings slide into one another and the brass crash, but it works. It’s the musical equivalent of watching a traffic jam, engines stall, horns blast, people shout, but if you step back, the experience has a relaxing effect.

The orchestra goes beyond music and harnesses a modern ability o create soind effects. Slaps. Bangs. Beeps. Both orchestras are swimming in sound effects.

The orchestra effectively recreates the sound of water in a way that is profoundly musical. Melodies are fleeting and the crash of competing bars is compelling.

I have never been more thrilled by a headache in my life. (And I truly did have a headache.)

In Least Like the Other, the American dream comes in conflict with itself. Despite painting a world of fragmented and fleeting ideas, Netia Jones and Brian Irvine have created a complete thought.

The ending is as unresolved as every movement of Irvine’s music, as distracted as every scene of Jones’ staging, and as tortured as every note song by Ni Fherraigh.

In Least Like the Other: Searching for Rosemary Kennedy, the picture-perfect farce of Camelot dissolves into the shuttered face of the Kennedy curse. In the story of Icarus we are warned about the boy who flew too close to the sun, but what ever happened to the daughter?

Advertisements

AdvertisementsAll photos are promotional photos from Irish National Opera and Pat Redmond.

-

Review: Matthew Bourne’s Sleeping Beauty; A Fever Dream Fairytale

Matthew Bourne is a household name, even to those outside the dance community. He is often hailed as one of the UK’s most famous choreographers. And, indeed, he has had a number of key successes that have influenced the world of dance—namely a reimagining of Swan Lake as a gay romance.

So what went wrong? Why did I dislike Bourne’s take on Sleeping Beauty? It’s one of the most famous ballets in the world and it’s certainly a masterwork of Tchaikovsky’s. But did Bourne stray too far from the original text?

Bourne’s mega-successful reimagining of Sleeping Beauty returned to Sadler’s Wells to celebrate its 10th anniversary this year. But would it have been best to let this one rest?

The show bills itself as a “gothic romance,” though it is neither gothic nor romantic. Instead it reaches for modern relevance, but the tone already feels dated. It’s still under the spell of the zeitgeist from 10 years ago. It is neither comedy nor tragedy. And with all the missed steps and botched timing, it doesn’t even dance to the beat of its own drum.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsAt best, Bourne’s Beauty mixes metaphors. It’s in-cohesive and startling. It mistakes shocking reveals with meaningful plot.

Sitting in one of the world’s most famous dance theatres, Sadler’s Wells, I spent the entire performance struggling to figure out this show’s identity.

Is it a panto?

The curtain rose to a promising start. The wicked fairy, Carabosse (or Maleficent in Disney speak), performing a menacing shadow dance, foreshadowing their power play against baby Aurora.

But then..a puppet.

A tiny baby bursts through the curtains, its limbs flailing as it bounces up and down. A few stifled laughs ripple through the audience. Then, as the puppet baby awkward crawls across the stage, the audience leans comfortably in on the joke.

The physical comedy continues. As dancers emerge, minor characters distract with gimmicks.

The audience is laughing, but these are cheap laughs.

After a sleeping spell that last 100 years, we return for Act Two in present day. This would be a clever wink and a nudge had the performers not over-egged the pudding with overly obvious cell phone usage and a few too many selfies. The cell phone shtick continued long after the chuckles subsided.

In battle scenes I use all my self control to resist shouting “he’s behind you!”

I can’t help but wonder, is this a panto?

Is it even a ballet?

Given Sleeping Beauty is one of the world’s most famous ballets and the casting boasts top billing for ballet dancers, it’s reasonable to expect a ballet.

Instead, Bourne’s Beauty is a long-form contemporary dance piece with occasional ballet poses. This seems to be the expressed intention: “contemporary dance theatre.” However, the execution misses the mark. Group numbers are not synchronised. Counts are missed. The dancers seemingly lurch between dance styles desperately searching for a sequence that works.

Fortunately, there are some beautiful ballet sequences, courtesy of Aurora, on this night performed by Katrina Lyndon. At the beginning of the second act, two fairies attempt to awaken Aurora, who is under a sleeping spell. The following pas de trois is elegant and delicate. Aurora nearly lifts herself to match the fairies’ steps, though falls into their arms without completing a melody. Aurora’s falls are graceful. The fairies, catching Aurora, swoop her into a lift, sometimes a pose, but always creating a silhouette of the young, lively Aurora before the spell.

These stunning ballet sequences are the saving grace of a performance full of some sloppy and inefficient dances.

The emotional high point of the first act is the famous Roses Waltz, you know, the one whose melody lends itself to “Once Upon a Dream,” from Disney’s 1959 animated Sleeping Beauty. What begins as a waltz turns into a jazz sequence that has been cross-pollinated with contemporary.

Unforgivably, the counts are off. The waltz is one of the simplest rhythms in dance. A waltz repeats even bars of 3 counts. 1-2-3, 1-2-3. Watching the Roses Waltz, it appears there were more than 3 counts in this waltz. Perhaps the introduction of jazz inspired improvisation. However, as a group number, this rose garden wilted.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsIs it even Sleeping Beauty?

This is a shock factor Sleeping Beauty.

At times the story is hanging on to the original synopsis by the skin of its teeth (no spoilers, only veiled references). These plot twists create effective audience reactions, but fail to coalesce into a cohesive plot. Perhaps I should have had another glass of wine before the performance.

To be fair, it all starts out fine. The prologue is dense. Before the end of the overture, Aurora’s parents must plead with Carabosse for a child, give birth to Aurora, welcome the child to court, and receive the curse from Carabosse.

While most ballets require pre-reading to understand the action on stage, this production cleverly projects the synopsis onto the curtains during the prologue and the overture.

The most noticeable change sees traditionally female characters performed by men. Caraboose is replaced by her son after the prologue and the Lilac Fairy become the Lilac Count. Bourne’s company is on-brand as a male-forward cast. These are overall welcome changes, but largely emphasise existing concerns about the male gaze.

Unfortunately, this reimagining fails to address a glaring concern in the original story—female agency. Despite a surprise middle point for Aurora and a slightly-altered ending, Aurora’s fate is at the will of her male counterparts. The maleness of decision making is reinforced in a plot twist by Carabosse’s son just before the climax in Act Two.

With the same beginning and largely the same end, is it worth all that fuss for a few plot twists?

Advertisements

AdvertisementsIs it even any good?

Leaving the theatre, some audience members were chatting positively. Often these audience members were discussing specific moments or key visuals rather than the work as a whole.

The show has clearly engaged a younger audience. It has also clearly been very successful. I support all enthusiasm for dance. So if this is for you, turn the music up. And if it’s not, we are blessed with a forthcoming production of Sleeping Beauty from the Royal Ballet.

Just as Aurora must be asking herself at the end of the story, was it worth it to reawaken Sleeping Beauty after all these years? Perhaps Matthew Bourne’s Sleeping Beauty should have stayed in bed.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsAll images are promotional photos from Matthew Bourne’s New Adventures and Sadler’s Wells.

-

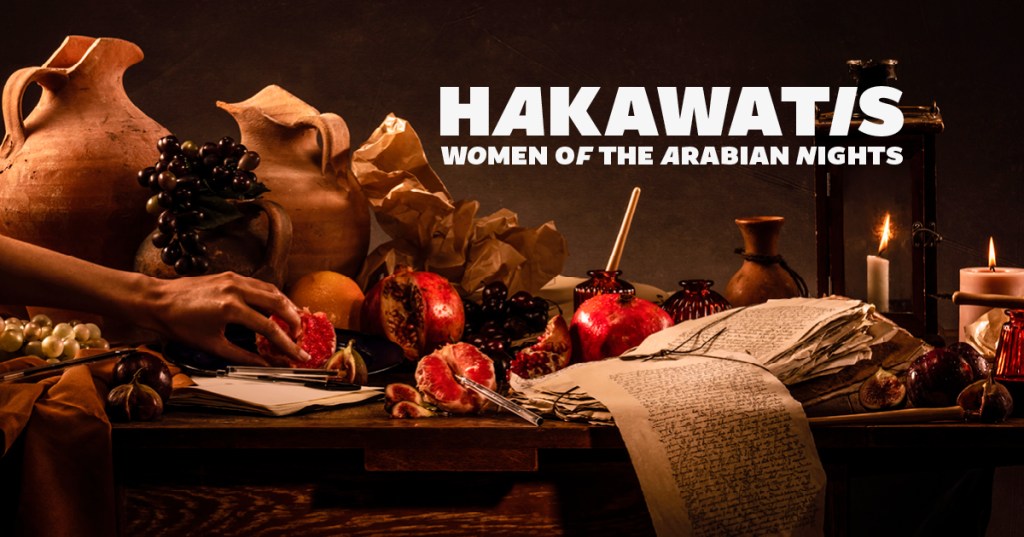

Review: Hakawatis, Women of the Arabian Nights; Intimate Storytelling in Female Gaze at Shakespeare’s Globe

“The whole play is a female orgasm,” playwright Hannah Khalil reveals in a post-show Q&A.

Earlier that night, the first “line” in Khalil’s new play, “Hakawatis, Women of the Arabian Nights” is an enthusiastic moan, the beginning of an intimate night of storytelling.

“This isn’t the male orgasm that goes [draws fingers up to the peak of a mountain and back down],” Khalil elaborates. “This is a [motions fingers in hypnotic circles] orgasm.”

The first scene is deceiving. Hakawatis could easily fit the three act structure of, to use Khalil’s words, the male orgasm. A scorned king seeks revenge when discovering his wife’s infidelity (beginning) by marrying a succession of virgin girls night after night (middle) before murdering them after consummating the marriage (ending). A quick payoff.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsInstead, the opening scene becomes the frame story for the tales to come. When a young girl named Scheherazade is married to the enraged king, she disrupts these gruesome nightly rituals by telling the king a story and then promising another if she’s saved. It’s a story within a story.

The next night, Scheherazade tells another story which finishes precisely where the next night’s story will begin. The stories interlock, like rings in a chain, weaving in and out of each other. Zooming out to the first frame, these stories promise Scheherazade’s safety…at least for that night. But who is writing these stories?

If this story sounds familiar, it is because the play’s source material is “Arabian Nights” or “1,001 Nights.” Though, Khalil has flipped the script. Here, the king is offstage and infrequently invoked.

Instead, the women of the Arabian Nights are centre-stage. The women craft stories that they sneak to Sheherezade from a sequestered room of stone and candles beneath the palace.

There is no story without a storyteller. This night, tucked into the candlelit Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe, 5 storytellers bring to life the ancient tradition of storytelling with the most innate tools—the voice, the body, and simple everyday items at hand.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsThe real success of “Hakawatis” is the chemistry between these 5 women. As the women develop stories they banter and they disagree, they encourage and they fall into very human emotional traps. This interplay creates a dynamic collection of contradicting and complementary stories sculpted by women as unique as the tales they tell.

“The first story, the one about the fisherman and the ‘gin’ [genie]—is entirely improvised,” reveals Khalil in the post-show Q&A. “It says in the script, ‘to be made different each night.’”

This is the moment the play sparks to life, when the flame is lit.

While the remainder is scripted, this improvised entry into the world of the hakawatis (meaning “storytellers”), draws me in and has me waiting with baited breath to witness a world painted for the first time from nascent words breathing their first exhale.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsThis breathing is underpinned by the show’s rhythms. With drumming and sliding violin riffs, onstage musicians create an atmosphere to suspend disbelief. The musicians set an audible heartbeat to each story that quickens and retreats, guiding the audience to believe their ears.

Director Pooja Ghai conducts a rhythm of her own. Ghai expertly builds tension in each scene, easing in slowly before quickening pace and bouncing between storytellers. At times there is chaos and confusion before arriving at a peak, lingering, and then releasing. In Ghai’s direction there is always a pay-off. Each story lands a punchline, crashes into a shocking reveal, or intrigues with an unexpected ending.

In “Hakawatis” Khalil and Ghai have crafted a play of nesting stories that warm and weave. In an age of feminist retelling of the Classics, with Madeline Miller’s Circe and Natalie Haye’s Pandora’s Jar, Hakawatis is refreshing in its approach. Stepping outside of the Western Classics, Khalil brings a female gaze to an Eastern relic, “Arabian Nights,” in a meaningful and satisfying reimagining.

“Hakawatis” is a candle that flickers, burning bright then waning. Its flame reaches upwards to an imagined escape before settling deep and stout on its wick. Its light is warm and delicate, yet potent and enduring. Like a moth to a flame, Khalil’s enchanting storytelling draws us in and smoulders.

All images are promotional photos by Ellie Kurttz (2022) and Shakespeare’s Globe.

Advertisements -

Best of the Year: Review: My Neighbour Totoro; Some High End Puppets

The audience gasped.

And then gasped again.

And another gasp.

As I watched Royal Shakespeare Company’s world premiere production of My Neighbour Totoro, the audience came to life around me, reacting, laughing, and smiling at this triumph on stage.

How did they do it?

Puppets.

Music.

Small details. — leaning into those little moments in life that make everyday magic.

Expectations were high walking into the Barbican Centre. The film that lends the stage show its name and story, My Neighbor Totoro, is frequently listed near the top of Best Films of All Time countdowns. The stage production opened to high praise. Tickets quickly sold out after a few key rave reviews, including a 5-star review from The Guardian.

And Totoro delivered.

It’s a simple story at its core. The 1988 Studio Ghibli cult classic tells the story of two young sisters, Mei and Satsuki, who move from the big city to the Japanese countryside with their parents to revive their mother’s failing health. Set in the 1950s, it’s a romantic portrayal of Japan, its culture, its spirituality, and its people. The show’s larger themes balance the heaviness of human fragility and the hopefulness and joy of a child’s mind. In this range, somewhere between the weightlessness of hope and the depth of fear, Totoro strikes a resonant emotional chord.

AdvertisementsTotoro is an atmospheric piece of theatre. The story itself is quite light on plot. Think about it—how do you remember the film? Ask someone else what they remember of the film. What you’ll find is most people remember moments and feelings.

Theatre creates moments like no other art form. Totoro is a buffet of delicious moments with all the right ingredients.

Which leads us to the puppets. If you can believe we are this far into the review without mentioning the puppets!

The puppets are extraordinary. The spirits and the creatures of the 2D anime roar into life in 3D, dynamic figures that quite literally fill the entire stage.

And that’s when the audience began to gasp.

When Mei and her sister Satsuki, arriving in the village for the first time, they discover creatures while exploring their new house. Gasp.

When Mei is playing in the garden and encounters her first little spirits. The room breathes in collectively then giggles.

When Totoro first appears on stage… this is the moment…you can hear audible delight, ‘wow’s dance around the auditorium.

And my personal favourite and perhaps one of the most iconic moments from the film…

When the cat bus arrives at the bus stop.

(No spoilers. I won’t describe the puppets in too much detail, but they need to be seen to be believed.)

It’s these moments of childhood imagination brought to life almost impossibly that make Totoro dazzle.

AdvertisementsThese puppets are colourful, they’re intricate, and they’re enchanting—I can’t look away. I want to watch them move, study their features, and invite them in.

They’re also larger than life. Improbable, the creative company that crafted and gave life to these puppets, built the characters of Totoro in the legendary workshop of Jim Henson, of Muppet fame, in LA. I first saw Improbable’s work in English National Opera’s production of Satyagraha last year. The consistency and quality of Improbable’s work is unparalleled. In my Jennifer Coolidge voice, “Those are some high-end puppets.”

But even though these puppets are creatures from a spiritual world, they never feel like monsters. They feel safe. This is partially achieved by expert puppeteers onstage, dressed all in black, making the puppets dance with levers and strings. It’s a peek behind the curtain that, paradoxically, adds another layer of magic. If you’re lucky enough to attend, stay tuned for a bit of cheeky humour from the puppeteers themselves throughout the evening.

For me, the final wave of a wand that pulls off the magic trick is Joe Hisaishi’s music.

Joe Hisaishi is the John Williams or the Alan Menken of anime. (I will spare you my passionate soapbox about how Joe Hisaishi’s score to Howl’s Moving Castle may be one of the most beautiful film scores ever written.)

In fact, it was Joe Hisaishi himself who brought Totoro to stage. Dreaming for years and years to bring a Studio Ghibli film to the stage, Hisaishi was looking for the right collaborator. Of all the internationally acclaimed films in Ghibli’s catalogue, Hisaishi wanted Totoro specifically. Finally, Hisaishi decided to collaborate with the Royal Shakespeare Company, working hands-on over years to perfect and polish this existing masterpiece. It should be no surprise then that, with composer as executive producer, the music is a central figure in the show.

A light hearted orchestra soundtracks the entire performance from onstage. They perform from floating platforms, draped in the trees, the bird nests, and the moon, almost embedded in the set upstage.

AdvertisementsHisaishi’s music itself is gorgeous. It’s at times joyful and playful and other times strained and yearning. Though the score for Totoro is inked with a deep heartfelt and soulful undercurrent. The music, without us noticing, easily guides the hopefulness of the story from our eyes to our hearts.

The Totoro Ending Theme is endlessly singable. What a way to exit the theatre! The curtain raises again as the live band sings out those 3 staccato notes— To-to-ro-To-to-ro — as they dance between the audience singing along (and sometimes dancing) with the house lights up.

This show needs to be seen. It’s sold-out run at The Barbican is a testament to its success. We can only hope for a UK tour, a West End transfer, or even a Broadway run.

My Neighbour Totoro is the most incredible piece of theatre I saw in 2022. And I wish you the opportunity to experience it as well.

Totoro is a hit.

Advertisements

All images are promotional photos from Royal Shakespeare Company and the Barbican Centre, by Manuel Harlan.

-

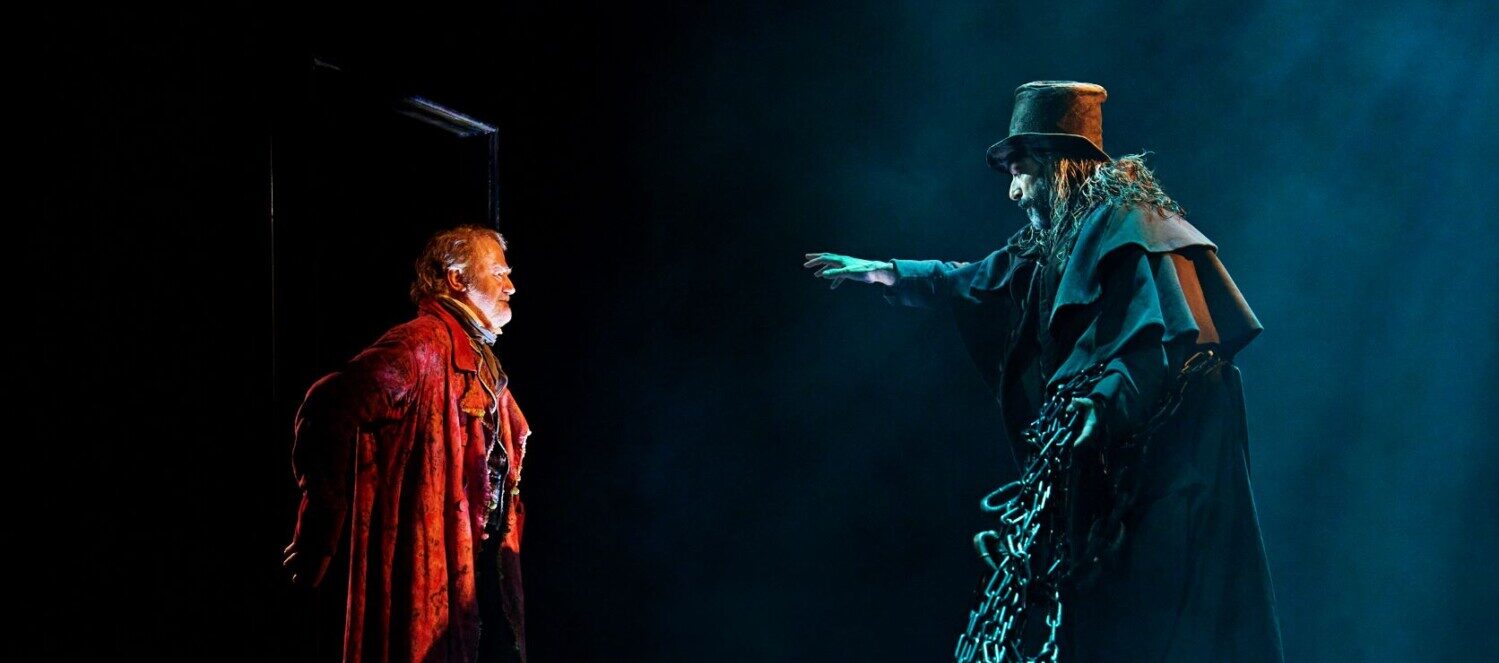

Review: Jack Thorne’s A Christmas Carol at the Old Vic; The Gold Standard of Scrooge

If I thought there were too many productions of The Nutcracker, where do I begin to count the number of A Christmas Carols in London?

If there were as many Christmas Eve ghosts as there are productions of the Dickens classic, Ebenezer Scrooge might not have made it to Christmas dinner.

So, of all the gifts under the tree, which do you choose to unwrap?

For me, the Old Vic’s A Christmas Carol is my favourite.

Matthew Warchus’ and Jack Thorne’s beloved production of A Christmas Carol is equal parts traditional storytelling and innovative theatre. Here you will step into the world of Victorian London Charles Dickens…

And then there’s magic. Jack Thorne is perhaps best known for Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, a feat of innovative staging and lighting. Here, you’ll find Thorne’s theatrical signature with stage mechanics that twist reality in front of our eyes and lighting that both confuses and illuminates. Don’t expect any spells or flying broomsticks, but do expect a few tricks.

Though, most importantly, at the centre is the story itself based on Charles Dickens’ novel. At the Old Vic, A Christmas Carol maintains the heart of the story, while dazzling with modern theatre magic. Expect traditions, but expect something new, as well.

Curious what’s underneath the wrapping paper? Read on to count down 3 reasons why I’ve chosen Old Vic’s A Christmas Carol as my festive pick.

What makes this special? Let’s have a look!

Advertisements

Advertisements4. The balance between darkness and hope

Where some productions can lean too deep into the macabre while others present glib optimism, this version of A Christmas Carol manages to successfully balance the plot’s darker themes with the story’s overarching optimism.

Here, the characters lead. And I think that’s the key.

This is the full Dickens experience, complete with Mr. Fezziwig’s Christmas Ball and lost love. Although other minor characters and subplots also step forward. Family members and friends bring layers of nuance to the story. This ultimately makes the redemption arc more rewarding.

Advertisements

Advertisements3. The music & magic of timeless Christmas

While this A Christmas Carol isn’t a musical, you’ll still walk away singing. Christmas carols weave in and out of this story. Carols welcome you when you walk in; they hold the transitions between scenes; and carols lead the celebration on Christmas Day.

And it’s not just voices! A string quarter welcomes you to the theatre and a bell choir chimes in throughout the evening. While the melodies are familiar, moving between strings, voices, and bells creates a richness and a texture to the sound.

And then there’s the finale…There is something uniquely emotional about singing Christmas Carols together. Even the Scroogiest Scrooge can’t resist softening at the familiar tunes. In its finale, the bell choir and the audience-as-chorus warms the heart and makes me believe in Christmas again.

2. Jack Thorne’s production & stage wizardry

Like the best magic, it’s the slight of hand that makes a trick come to life. With a detail so small, our minds easily skip over the slight of hand to be awed and impressed by the end result.

Thorne’s production is full of small turns that create onstage illusions. Set pieces easily transform. Light refracts and distracts. Set pieces appear. Ghosts appear and disappear. The whole experience feels like it’s floating in the middle of the theatre.

The brilliance of Thorne’s production is its simplicity. These aren’t sweeping set pieces and pyrotechnics. Instead, these tricks are confident enough to step back and let the story take centre stage.

And that’s what makes this show so easy to watch. It’s as smooth as watching a movie.

1.A Magical Christmas Morning

If you’ve seen A Christmas Carol at the Old Vic, the memory will most certainly come to mind. And, if you haven’t, let me not spoil it.

Instead, let me say, the atmosphere of the finale is all-consuming. You’ll feel it in your body and in your heart. It’s joyful. It’s celebratory.

Scrooge’s redemption is hopeful and heartwarming in such a genuine way. This isn’t a glib, cookie-cutter happy ending. All the real human emotions and character nuances build to this moment and it is utterly satisfying.

Have you seen Thorne’s Christmas Carol at the Old Vic? What did you think? Or, have you seen A Christmas Carol near you?

As my last post before the festive weekend, let me take this moment to wish you a very happy Christmas. And may your Christmas Eve be more peaceful than Scrooge. …. deep breath… God Bless us, every one!

Fancy another Christmas review? Try English National Opera’s It’s a Wonderful Life, the opera! or the Grinch-themed drag show Who’s Holiday starring Miz Cracker from RuPaul’s Drag Race.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsAll promotional images are by Manuel Harlan and the Old Vic.

-

Review: Royal Ballet’s The Nutcracker; Practically Perfect Christmas Magic

Is there a more ubiquitous musical tradition than The Nutcracker at Christmastime? Tchaikovsky’s music twinkles alongside Christmas lights around the world. Many young dancers look forward to performing at its Christmas Party. Its musical motifs decorate adverts, movies, and social media all season.

But how do you pick which Nutcracker to buy a ticket to? London Tube stations are a gallery of Nutcracker posters. And it seems there are as many productions of The Nutcracker as there are American candy shops in London.

By far, The Nutcracker at the Royal Opera House is my pick. Peter Wright’s production captures the joy of experiencing Tchaikovsky’s brilliant ballet as a child, while still feeling adult and fully formed. It avoids childish tropes without compromising the magic of its story.

But before I get ahead of myself, let me count down my top 3 reasons why the Royal Ballet’s The Nutcracker is my favourite. It’s an advent calendar of a review, if you will.

Advertisements3. Focus on the Dancing

At its core, The Nutcracker was written for dancing. And dance it does.

However, do not expect rich, decadent set pieces like an opera or a stage full of whimsical props like a pantomime. Instead, the set is made of a festive backdrop and borders with a few key props. Here the wide open floor is expertly filled by the Royal Ballet dancers, with space to leap, lift, and delight.

The dancing is technically brilliant. It is skilled and executed perfectly. The Royal Ballet has a high standard of dance, which The Nutcracker upholds.

The choreography is equally brilliant. During the Waltz of Snowflakes, the dancers swirl and mark formations that recreate a snowstorm. During Act Two’s carousel of curio dances in the Kingdom of Sweets, pairs perform exquisite pas de deus and lifts that showcase their athleticism.

For me, the standout of the night is The Nutcracker’s pantomime recreating the fight with the rat king. In this scene, The Nutcracker, performed by Benjamin Ella the night I attended, recounts the drama of Act One to the Sugar Plum Fairy and the Prince. Despite performing onstage alone, The Nutcracker is captivating when blending the expressive technicality of his choreography alongside the didactic drama of miming. He tells a story without words, showing the power of dance.

It wouldn’t be The Nutcracker without the next generation of ballet students performing. Students from White Lodge in Richmond, the Royal Ballet School’s academy for younger students, bring hope to the future of ballet. After a few years of cancelled or scaled back performances due to Covid-19, it is a joy to see the young dancers on one of the most impressive stages in the world. For many students, this is their first year performing at the Royal Opera House. You can feel their joy.

Advertisements

2. Atmospherically between a German storybook (its setting) and Russian Romanticism (its creation)

Wright’s production atmospherically lands between its setting, a German storybook, and its creation, the Romantic movement in Russia.

The ballet is based on a much darker, German fairytale by E.T.A Hoffman titled “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King.” The dark, almost gothic nature of Hoffman’s story is dramatic enough for the stage. Though translated to a ballet, its levity is lifted, while maintaining its original setting in an upper-middle-class German family.

The Royal Ballet translates this world onstage in a wholesome, 19th century aesthetic that fits neatly into a storybook. The grandfather clock and the great German tradition of a Christmas tree feel familiar, but of its time. The costumes with the overcoats and buckles are charming. The set recreates German Rococo swirls and designs throughout the stage. It’s the world of German fairytales without the grim outlook.

This setting blends perfectly with the Russian Romanticism. Tchaikovsky defined the Romantic movement in Russia. While his other ballets, Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake, may better capture this aesthetic, The Nutcracker still highlight’s its features. The music follows the emotional landscape of an individual on a journey through trial, fantasy, and dreams.

Taken together, it creates an atmosphere of timeless tradition. This is as close to a recreation of its premiere as you can get.

Advertisements

Advertisements- A Minor Character Takes Centre Stage

In its first performances, audiences hated The Nutcracker. Theatre goers felt there was a disconnect between Act One—the Christmas Eve party— and Act Two—the Kingdom of Sweets. Even today, Act One is plot heavy and fast-paced. Act Two, meanwhile, is slower with seemingly no story.

The Royal Ballet had a big problem to solve trying to be faithful to a hated premiere.

*Cue Drosselmeyer.*

In many productions, Drosselmeyer is a minor character. At worst, he is a Councilman that appears simply to give Clara the fateful gift of the Nutcracker. At best, he is a magician that brings spectacle to the family Christmas Eve party.

In Wright’s production, Drosselmeyer is the golden thread that weaves Acts One and Two together.

The production opens in Drosselmeyer’s workshop. We see him putting the finishing touches on the nutcracker as the overture trumpets fanfare. During the Christmas Eve party, Drosselmeyer pulls the strings as gifts unwrap and dancers dazzle the party guests.

But Drosselmeyer doesn’t exit stage right when Clara receives the Nutcracker. Instead, Drosselmeyer remains onstage as Clara and the Nutcracker hop on their sleigh into the Kingdom of Sweets.

Then, in Act Two, Drosselmeyer appears to keep the magic going by directing the showcase of delicious wanderlust dances of Act Two.

Besides providing wonderful choreography and miming, Drosselmeyer’s presence adds a layer of magic sprinkled like snow over the entire performance, almost as if he’s Father Christmas.

Have you seen the Royal Ballet’s Nutcracker? Did you feel the magic as well? Or, has another Nutcracker captivated you this Christmas? Let me know in the comments below.

Advertisements

AdvertisementsAll images promotional materials from Royal Opera House. Promotional photos by Alastair Muir and Tristram Kenton.

-

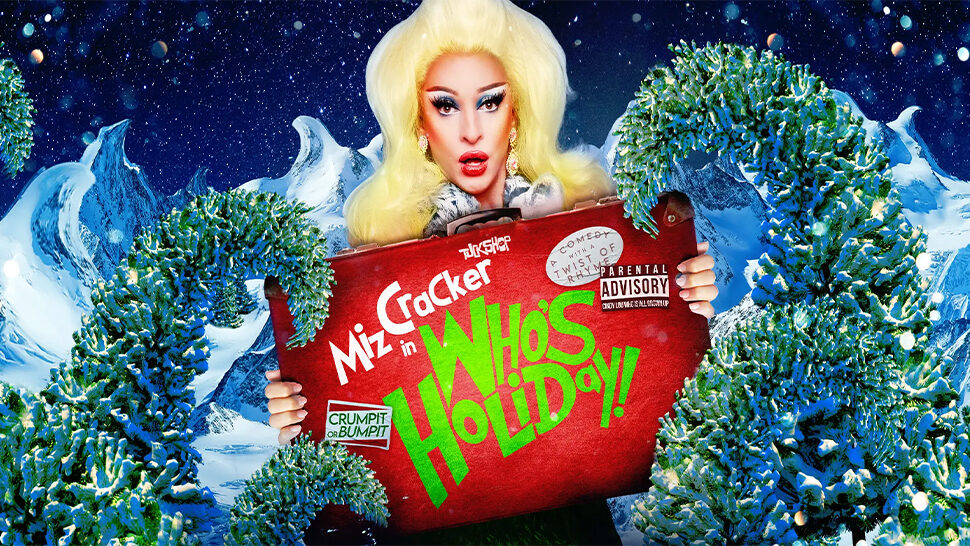

Review: Who’s Holiday? Miz Cracker is Crackin as Cindy Lou Who

The Grinch stole Christmas then gave it right back;

Cuz that Cindy Lou Who, she looked like a snack.They flit and they flirt and they snog with such glee

That the who’s in the audience ask “what did I see?”Cindy’s grown up, as you’ll soon find out,

This clever drag parody is the perfect night out.

Miz Cracker is camp as she rhymes through her panic,

Cue the music and she’s down just like the Titanic.She raps and she sings with an insult or two,

But this Cindy is sweet, she just doesn’t like you.Matthew Lombardo’s writing is smart and quick and engaging.

It glitters with tinsel and lights in this festive staging.Though Cracker is best when she’s just off the cuff,

Forgetting her lines, her ad libs are chuffed. Advertisements

AdvertisementsShe had a stiff start, but warmed up quite quickly,

Then the raunchy jokes start and their laid on quite thickly.This show is for grown-ups, so tuck the kids in,

Then hop in the sleigh with a few shots of gin.At the top of Mount Crumpet is a one-woman show,

with white stuff on the stage and you know it’s not snow.The show takes a turn about halfway through,

It gets dark, it gets real, but it doesn’t stay blue.

It’s a show full of heart, though it is a bit twisted,

Your heart will grow and your spirits, lifted.It’s the drag queen story time your hometown’s afraid of,

But the future liberals want, so let’s show ‘em what we are made of.If Miz Cracker invites you to her Christmas Day,

Say, “yes”— “Who’s Holiday” makes this Yuletide gay.

All images promotional materials from Southwark Playhouse and TuckShop UK. Promotional photos by Mark Senior.

Advertisements -

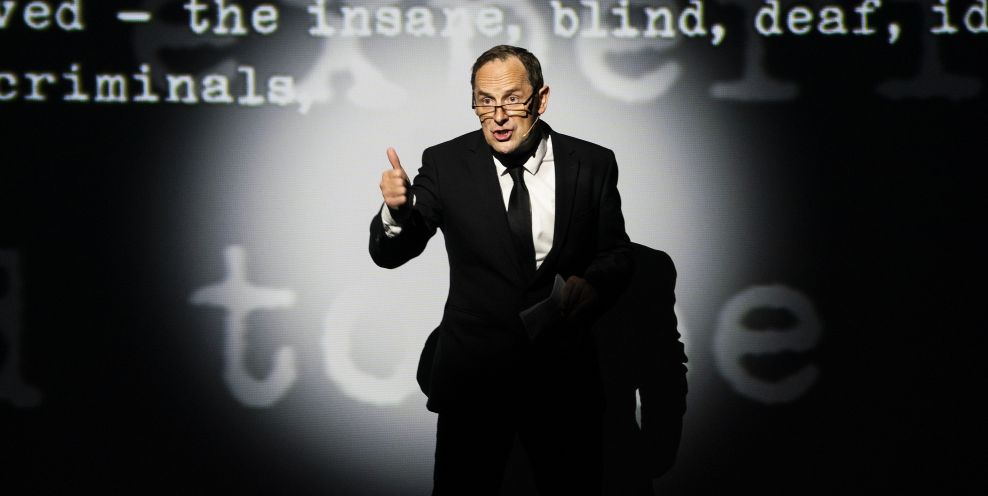

ENO’s It’s a Wonderful Life is Wonderful, but not Very Festive ★★★

Tonight is the UK premiere of It’s a Wonderful Life, the opera. Frank Capra’s 1946 film of the same name has the emotional drama to make a good opera, but, on stage, lacks the sparkle to make Christmas magic. Fortunately, Aletta Collins’ production creates a bright and whimsical Americana aesthetic that occasionally shines through this depressing Christmas classic. It’s a 4-star opera, but a 3-star Christmas show.

For fans of the film, the opera is a near play-by-play of the film. From Bedford Falls to Pottersville to the Bailey’s Christmas Eve party, the audience will find familiar faces and places on stage—with one key difference.

Clarence, the clumsy and loveable angel from the film, becomes Clara, an earnest and meddling soprano in the opera. Danielle de Niese’s Clara is a pleasant and light soprano who balances nicely with Frederick Ballentine’s wistful tenor. The angels and the Bailey family form an inviting ensemble with convincing acting. As a whole, it’s an enjoyable cast. Yet, call me a Grinch, no one stole the show.

If this is your first Jake Heggie opera, expect a night of musical theatre. Heggie’s score is a blend of vaudeville jazz, patriotic trumpets, and Christmas melodies. Punchy dance routines fill Bedford High’s graduation dance and barber-shop quartets sidestep hand-in-hand across the stage. It feels right at home in London’s West End. It’s the least operatic opera I’ve seen. It’s easy to digest and enjoyable, albeit a bit saccharine.

AdvertisementsConductor (and long-time Heggie collaborator) Nicole Paiement elevates Heggie’s energy. Paiement’s conducting creates peaks and valleys that make dreaming sequences feel hopeful and glittering while underscoring the anxious melancholy of Bailey’s financial woes.

Sounds fun, right? Unfortunately, the plot is a lump of coal for Christmas. The world of George Bailey is depressing. It’s a show about the false nostalgia of dreams that never come true. Potter, the domineering businessman, looms over the show (with a velvety and enticing baritone, I might add).

In December 2022, the forthright presentation of a rapidly devaluing currency and a housing crisis leave me worrying about the cost of living instead of celebrating the festive season. With ENO’s recent funding cuts, we can only hope this town comes together to save the day as they did with George Bailey.

It’s a Wonderful Life is more Blue Christmas than White Christmas. The show has some moments that glitter—the dance-a-long Mekke Mekke and the sparkling Auld Lang Syne sing-a-long finale–but as the bright snow turns to grey slush in the street and I return to work after writing this review, I can’t help but think that Christmas is just another bank holiday after all.

AdvertisementsAll photos by Lloyd Winters as part of English National Opera Press Pack.

Advertisements

- Review: 2:22 starring Cheryl; A Ghost Story that’s, ironically, human

- Review: Orlando starring Emma Corrin; Stylish but Self-conscious

- Review: Least Like the Other: Searching for Rosemary Kennedy; “Lobotomy: The Opera”!

- Review: Matthew Bourne’s Sleeping Beauty; A Fever Dream Fairytale

- Review: Hakawatis, Women of the Arabian Nights; Intimate Storytelling in Female Gaze at Shakespeare’s Globe